Young Koreans are 'taking breaks' from their jobs — and their parents aren't sure when they can retire

전체 맥락을 이해하기 위해서는 본문 보기를 권장합니다.

"I don't feel much inconvenience in my daily life," Roh, 30, said. "I usually eat at home and rarely go out, so I don't feel a strong need to earn more money."

"Due to my lack of experience, I feel like I'm facing an entry barrier," Ham said. "Job openings hardly go public, and employees are largely hired through connections. So, I'm currently taking a break to think about what I want."

이 글자크기로 변경됩니다.

(예시) 가장 빠른 뉴스가 있고 다양한 정보, 쌍방향 소통이 숨쉬는 다음뉴스를 만나보세요. 다음뉴스는 국내외 주요이슈와 실시간 속보, 문화생활 및 다양한 분야의 뉴스를 입체적으로 전달하고 있습니다.

![[GETTY IMAGE]](https://img4.daumcdn.net/thumb/R658x0.q70/?fname=https://t1.daumcdn.net/news/202507/17/koreajoongangdaily/20250717093326318bhor.jpg)

For nearly two years, Roh Jae-woong has been living with his parents, taking part-time jobs, after his kitchenware business quietly folded.

Although he feels anxious about the future — especially concerning home ownership and marriage — he remains unwilling to make significant efforts to resolve these concerns. He's not the only one.

“I don’t feel much inconvenience in my daily life,” Roh, 30, said. “I usually eat at home and rarely go out, so I don’t feel a strong need to earn more money.”

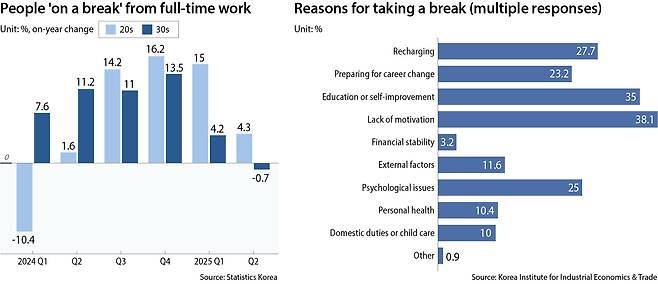

Roh is one of the fast-growing number of young people in the Korean labor market that has exited the work force, posing a significant challenge on Korea's shrinking and aging population. A total of 690,000 people in their 20s and 30s said they “were on a break” from work in June, accounting for 5.5 percent of the age group.

But experts warn that this growing young, economically inactive cohort could be holding older generations back — weighing heavily on their expenses, purchasing power and retirement timeline.

Growing 'kangaroo tribe' Thirty-two percent of Koreans born between 1981 and 1986 still live with their parents, according to a March report by the Seoul Institute, part of a growing “kangaroo tribe” who remain in the parental “pouch” for financial security. The trend is more evident in the greater Seoul area, where housing prices are more expensive: The figure there is 41.1 percent.

Meanwhile, the number of people in their 20s “taking a break” from the work force — defined as not having actively looked for a job in the past week for reasons unrelated to household duties, child care, education or illness by Statistics Korea — jumped sharply following the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

The proportion of employees and executives in their 20s declined from 24.8 percent in 2022 to 22.7 percent in 2023, and further to 21.0 percent in 2024 — a decline of 3.8 percentage points in two years, according to a survey research institute CEOScore conducted on 67 of Korea's top 100 companies by revenue.

One factor is the fact that the pandemic wiped out a number of jobs: New job openings at companies with at least 300 employees were 15.6 percent lower in 2023 than they were in 2019, according to Statistics Korea data.

![People line up to enter a job fair in Suwon, Gyeonggi, on July 9. [JOONGANG PHOTO]](https://img2.daumcdn.net/thumb/R658x0.q70/?fname=https://t1.daumcdn.net/news/202507/17/koreajoongangdaily/20250717093327296hyue.jpg)

Kids stay, parents pay

The growing number of young people taking a break is heavily impacting older generations, leaving them unable to retire as they shoulder the burden of supporting both adult children and their own parents.

The labor force participation rate of those in the 60s and above reached 49.2 percent in June, up 0.7 percent from the previous year, according to Statistics Korea data released Wednesday; those in their 20s fell 0.5 percent to 65 percent in the same period.

The trend is depriving young people of opportunities to build a proper career as they fail to timely acquire the skills necessary to improve workplace productivity, according to Lee Yoon-soo, an economics professor at Sogang University.

“That could ultimately drain the country’s social security expenditure, as these individuals could grow older without developing the capacity to increase their earnings in line with their abilities — a key factor in accumulating personal wealth,” Lee said.

Such prolonged breaks could result in increased social frustration, experts say, as delayed entry into the work force could impact an entire career trajectory by postponing key career milestones. Experts also worry that if such breaks extend too long, they may put young people at high risk of social isolation due to a lack of community engagement.

A similar phenomenon was observed in Japan in the mid-1990s following the burst of the country’s economic bubble earlier in the decade. As companies drastically reduced hiring to cut costs, many young people became part of what is now known as the “lost generation” — a cohort that faced chronic unemployment and job insecurity, which in turn contributed to the rise of radical ideologies.

Japan’s lost generation, estimated to number as many as 17 million, is still struggling to fully shake off the impacts of that period.

Some say the solution is better infrastructure in suburban areas, which could make working in those regions more attractive.

“To attract young talent to suburban areas from greater Seoul, cultural spaces and recreational facilities tailored to their interests, including new apartments, movie theaters and sport facilities where people can spend time after work need to be developed,” said Professor Woo Seok-jin, a professor of labor economics at Myongji University.

A vicious cycle of joblessness

But compounding the problem, the longer they stay out of the regular workforce, the slimmer their chances of getting in.

Korean companies increasingly prefer to hire experienced workers over novice employees. That preference is making it challenging for young people like Ham Seung-yeon, 26, to start a new career.

Ham, who double majored in French and business, worked in management consulting and tech before attempting to land a job in private equity. She met with several people in the industry without much luck.

“Due to my lack of experience, I feel like I’m facing an entry barrier,” Ham said. “Job openings hardly go public, and employees are largely hired through connections. So, I’m currently taking a break to think about what I want.”

Also in play is the fact that today's graduates are entering fields in which working conditions don't meet their expectations.

“Labor market mismatch has been a chronic issue that has not been properly addressed for many years,” said Son Yeon-jeong, an associate fellow at the state-funded Korea Labor Institute.

“Companies have taken on a cost-cutting approach, trying to reduce labor costs instead of developing talent to raise productivity,” Son said. “The poor working conditions that have been created and persisted since don’t match the standards of today’s younger generation.”

BY JIN MIN-JI [jin.minji@joongang.co.kr]

Copyright © 코리아중앙데일리. 무단전재 및 재배포 금지.

- 'Straight out of a drama': Valedictorian's mother caught breaking into school to steal exams

- Young Koreans are 'taking breaks' from their jobs — and their parents aren't sure when they can retire

- Alleged assault by Korean on Vietnamese in Hanoi photo booth sparks outrage

- Stray Kids collaborates with Tottenham Hotspur on new away kit

- Korean men, women have largest disparity on intention to have children

- Paths blocked, trains on hold, officials deployed as heavy rain batters Seoul

- DP urges gov't to shut the barn door on U.S. beef imports

- Top court acquits Samsung Chairman Lee Jae-yong of all charges in 2015 merger case

- Why Astro's Yoon San-ha clashed with Cha Eun-woo on new album: 'I gained more confidence'

- Pretend tourists, lavish meals, empty beaches: North Korea's new resort gets first foreign reviews