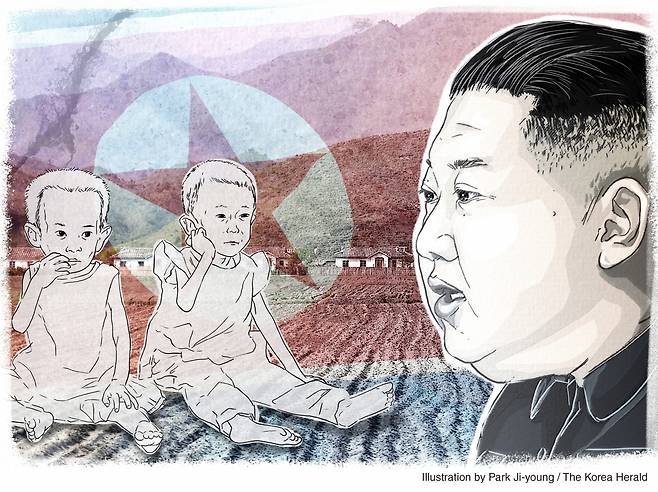

[NK Hunger] Kim Jong-un’s food politics: How food insecurity is leveraged to maintain regime stability

전체 맥락을 이해하기 위해서는 본문 보기를 권장합니다.

Cho Chun-hui, director of Good Farmers and an expert on North Korean agriculture, said the current agricultural policy was unrealistic, likening it to "squeezing water from a dry tree."

"In a nutshell, the North Korean authorities have only paid lip service to the importance of agricultural production, without making any investment to that end," Cho said. "In the absence of investment, the necessary facilities and materials for cereal production are unavailable, resulting in a continuous decline in agricultural production."

이 글자크기로 변경됩니다.

(예시) 가장 빠른 뉴스가 있고 다양한 정보, 쌍방향 소통이 숨쉬는 다음뉴스를 만나보세요. 다음뉴스는 국내외 주요이슈와 실시간 속보, 문화생활 및 다양한 분야의 뉴스를 입체적으로 전달하고 있습니다.

Shortly after taking power, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un said in 2012 that he wouldn’t have his people “tighten their belts again.”

He has pushed to overhaul the agricultural system and enhance crop yields since then, but food shortages have continued.

This year, the Kim regime has prioritized enhancing grain production among its 12 major economic goals.

The ruling party views agricultural challenges as a “life-or-death matter for the survival and development of the country, the destiny of the people and the future of the revolution,” the Rodong Sinmun, an organ of the ruling Workers Party of Korea and North Korea’s main newspaper, wrote in its editorial published in March.

The average annual grain production was 4.75 million metric tons from 2012 to 2014, but decreased to 4.57 million tons between 2019 and 2021, despite growing total demand since 2012, according to the South Korean government-funded Korea Rural Economic Institute.

South Korea’s state-run Rural Development Administration estimated that North Korea’s grain output dropped by 3.8 percent on-year to 4.51 million tons last year.

Food politics

The leadership’s focus on food security reflects its recognition of its crucial role in regime stability, experts on North Korean agriculture and economy said.

“Although the current food supply does not pose an immediate threat to the stability of the Kim Jong-un regime, food security has become increasingly vital in ensuring its stability,” said Jeong Eun-mee, a researcher at the Korea Institute of National Unification. “If the unstable food security situation persists, it could become a decisive factor that threatens the regime’s stability.”

Notably, North Korea held an unprecedented four-day party plenum dedicated to agricultural issues in late February and early March.

“The party plenary session serves as a message from the Kim Jong-un regime to its people, indicating their attention to agricultural issues,” said Yi Ji-sun, an analyst at the state-run Institute for National Security Strategy in Seoul.

For Kim, addressing food shortages could also allow him to carry out a buildup of military arms, his nuclear program, and the development of advanced weapons without enraging North Koreans who are suffering from a poor economy.

“Rice is a source of national strength and dignity and a significant foundation for development,” the Rodong Shinmun said in its editorial published on the front page on May 13.

The newspaper also set out the party’s goal of “making a breakthrough in achieving self-reliance and firmly securing the fortress of self-defense with rice” in a political article carried on the front page on March 18.

“Rice itself represents self-reliance, independence, and self-defense,” it read.

Jeong suggested that North Korea’s efforts to enhance food independence may signify Kim’s intention to adopt an assertive foreign policy stance.

Choi Eun-ju, a research fellow at the Sejong Institute, pointed out that Kim has strategically prioritized food production and enhancing living conditions in rural areas, where he can yield noticeable results more quickly than in sectors like heavy industry.

Kim can use his achievements as a means to showcase the regime’s commitment to its “people-first principle.”

“Kim seeks to convey the message that the country’s budget is being spent for the benefit of its citizens, demonstrating a willingness to undertake projects such as increasing food production and improving living conditions in rural areas. This is an image that Kim has consistently sought to cultivate,” Choi said.

“The people’s assessment of the leadership will vary depending on the results it achieves, and it may not be easy for Kim to attain tangible outcomes due to internal and external challenges. But if Kim continues to pursue this policy direction, it is unlikely to have adverse impacts on his leadership unless the country faces the worst food crisis.”

Return to 'calorie leadership'?

The North Korean leadership has had a long history of establishing and maintaining the regime’s stability and durability through the public distribution system, in what is dubbed “calorie leadership.”

In recent years, there appears to have been a return to this approach. The Kim regime has sought to tighten central control over the allocation and distribution of rice and other grains by restricting grain transactions at gray markets and selling grains at state-run food shops at below-market prices.

But the public distribution system that provides food and other necessities for the general public has barely functioned since the famine of the mid-1990s, which led to the bottom-up marketization of the economy.

North Korean authorities in 2003 allowed farmers’ markets to trade a variety of products, including crops harvested from privately cultivated fields.

But Kim Jong-un and his late father Kim Jong-il have since made several attempts to retake control over grain distribution, despite North Koreans’ reliance on the markets for survival.

“Kim Jong-un may employ a strategy of increasing people’s dependence on the North Korean regime for their food supply as a means to ensure regime stability. This could involve suppressing markets and restricting grain sales to state-run shops,” Yi said.

Regardless of intent, Kim's tightening of control over food would disproportionately burden the poor. In general, authoritarian regimes often prioritize policies that benefit powerful actors capable of resisting the regime, without considering the interests of others.

“The approach of the Kim Jong-un regime, characterized by tightening control over food and suppressing markets, has the potential to impose heavier burdens on vulnerable groups, such as the rural population, requiring their sacrifices. At the same time, it aims to minimize the impact on city dwellers and the elite class,” Yi said.

As an example, Yi pointed out that city dwellers who consume rice as their staple food might be less affected by food shortages compared to those in poverty who rely on corn, the price of which has shot up.

North Korea’s corn prices almost doubled to 3,300 North Korean won per kilogram on May 12, from 1,700 won in early December 2019, according to data provided by Asia Press International, a website in Japan that monitors the North Korean internal situation through clandestine local informants.

By official rates, 3,300 won is about $3.60, but it is about 40 cents on the black market that ordinary North Koreans use. A Seoul National University study estimated the average monthly salary in the North at about 560,000 won.

During the same period, rice prices rose relatively modestly, from 5,082 to 6,200 North Korean won.

N. Korea on wrong track

Addressing food insecurity is integral to maintaining regime stability. Some experts expressed optimism that North Korea had managed to identify the key challenges that need to be addressed during the four-day party plenum.

North Korea has presented revamping irrigation systems, manufacturing and providing new machines for agricultural modernization, reclaiming tidelands, expanding cultivated areas, and advancing agricultural science and technology as major tasks.

“The main tasks proposed by North Korea at the plenum are not merely cliche, but their repetition demonstrates North Korea’s struggle to resolve the problems,” Choi said. “Unless North Korea addresses these issues, it will be challenging for the country to increase agricultural productivity.”

But other experts warned that the leadership will not be able to improve crop yields without changing course.

Cho Chun-hui, director of Good Farmers and an expert on North Korean agriculture, said the current agricultural policy was unrealistic, likening it to “squeezing water from a dry tree.”

“The Workers’ Party of Korea upholds the slogan, ‘We serve the people.’ However, in reality, it does not serve the people, and it is rather moving in the opposite direction,” he said.

He agreed on the need for investment in infrastructure, machinery and supplies, but said it would not materialize without a change in approach.

“In a nutshell, the North Korean authorities have only paid lip service to the importance of agricultural production, without making any investment to that end,” Cho said. “In the absence of investment, the necessary facilities and materials for cereal production are unavailable, resulting in a continuous decline in agricultural production.”

Kim Young-hoon, a senior research fellow at the Korea Rural Economic Institute, underscored that reform alone would not be enough to significantly improve output.

“To achieve agricultural development, North Korea must seek capital from the international community as it currently lacks the necessary funds,” he said. “This highlights the importance of economic opening.”

The researcher suggested that North Korea should push for market-oriented reforms, including measures to incentivize farmers to enhance crop productivity and move away from the collective farming system. Reinforcing the role of markets in selling and purchasing grain would be also crucial.

Cho shared this view, saying, “North Korea can increase agricultural production and address food shortages only by activating markets. This would enable farmers to increase their incomes by selling their grains in markets and allow them to purchase what they need for farming.”

Kwon Tae-jin, a senior economist at the private GS&J Institute in South Korea, underscored that the best way to solve the North's current food shortages in the very short term is to open the borders and allow people to engage in market activities, rather than seizing control over the food supply

He said that once the North Korea-China border opens to a certain extent, North Korean merchants will be able to bring in food from China through unofficial trade channels, alleviating food shortages.

North Korea’s yearslong border closure and tightened control over markets have exacerbated food shortages. These measures not only restrict official food imports but also block the unofficial import of significant quantities of food.

“North Korea’s self-produced food by itself is vastly insufficient to meet the country’s demand without an adequate inflow of food from outside,” Kwon said, highlighting that imports were indispensable.

A lack of farmland, poor soil and terrain, and a short growing season prevent the country from achieving self-sufficiency.

“Fundamentally, North Korea will never be able to overcome food shortages if it continues to pursue its long-standing principle of self-reliance,” Kwon said.

This article is the final installment of a two-part series investigating North Korea's food shortages and the political and socioeconomic implications for the reclusive regime and people, as well as ways to put its agriculture on the right track. -- Ed.

By Ji Da-gyum(dagyumji@heraldcorp.com)

Copyright © 코리아헤럴드. 무단전재 및 재배포 금지.