[Column] Biden had a good January in Asia

Michael GreenThe author is CEO of the U.S. Studies Centre at the University of Sydney and Henry A. Kissinger Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). While there is a lot of anxious gloom and doom in Washington about China’s menacing rise, the reality is that Joe Biden had a very good month in the region. He can thank Xi Jinping for much of that, but definitely needs to give a nod to President Yoon in Korea, President Marcos in the Philippines, and the strategic foresight of the Asia Team he assembled back in Washington.

The stage was set in December when Seoul announced its first Indo-Pacific Strategy. This means that Japan, Australia, India, most of Europe and Asean and now Korea have chosen the framing originally introduced by Japan’s Prime Minister Abe Shinzo that the region must remain free and open with the implication of greater alignment among democratic stakeholders — and a rejection of Xi Jinping’s Sino-centric vision of a “Common Destiny” with it eerie echo of Japan’s 1940 Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. While Seoul’s strategy was carefully designed to address Korean national security interests in the region, it was also a huge win for Washington in two respects. First, strategic thinkers in Beijing for decades have quietly asserted that the Korean peninsula will naturally (and peacefully) fall into Beijing’s sphere of influence as it always has in periods of Chinese ascent. I first heard this argument from the most senior Chinese diplomats in 2005 and subsequently from strategic and international relations scholars in Beijing over the years. The friction between Tokyo and Seoul only reinforced Chinese leaders’ conceit that time was on their side on the Korean peninsula. The new Yoon strategy demonstrates that Korean interests and values hew closely with those of other major powers in the world also concerned about Beijing’s growing coercion and hegemonic ambitions. China does not feature as the reason for the strategy, but it clearly is. And second, Korea’s new Indo-Pacific strategy suggests that Seoul will do more to align its formidable assets with the efforts of other like-minded countries like Australia or the United States in terms of diplomacy, infrastructure financing and development assistance.

U.S. officials were busy with the U.S.-Japan alliance as well, referring to multiple summits and defense agreements with Kishida’s government in Tokyo as “Japanuary.” The focus was on setting up a framework to support Kishida’s new plan to grow Tokyo’s defense spending from 1 percent of GDP to 2 percent. This is not actually a doubling since the new accounting will use NATO standards and thus represent more of a 75 percent increase, but it is a big jump nonetheless and enhances deterrence in the region.

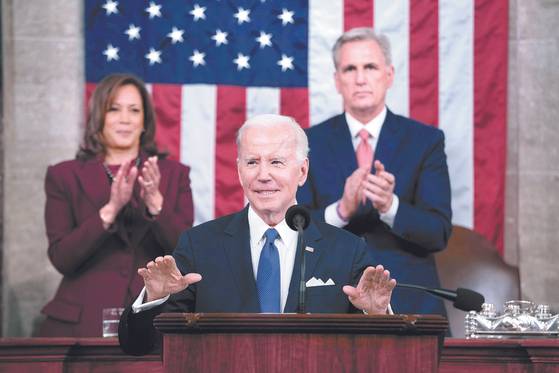

'U.S. President Joe Biden delivers the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress, Feb. 7, in Washington, as Vice President Kamala Harris and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy applaud. [AP/YONHAP]

India too benefited from a major agreement for capacity building with the United States. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modhi had explained to Biden back in March that Delhi could not sanction Russia because the Indian military was still so dependent on Russia for equipment. India’s strategy on China is also hampered by the attractiveness of lower-cost 5G networks from China’s Huawei and India’s own lagging tech industry. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan responded to all three of these problems with a major announcement on February 1 that the United States would assist India with the development of capacity in semiconductors, AI, and quantum computing. This tracks with U.S. efforts in Pillar Two of the U.S.-UK-Australia agreement to work in the same areas with Britain and Australia and similar agreements with Japan and Korea.

That same week, the administration also announced an agreement with Japan and the Netherlands to restrict the export of the most advanced semiconductor fabrication technologies like immersion lithography to China. Since the export control rules introduced in October by the Biden administration already restrict the flow of experts and not just technological information or devices alone, it will become increasingly difficult for China to maintain high end chip production or even design work behind things like the Apple iPhone. In other words, the ripple effect of this on China’s tech sector could be far more significant than the headlines reveal and will slow Beijing’s ambitions to dominate artificial intelligence, where advanced semiconductors are a key input. Overall U.S. trade with China remains quite high, but when Beijing’s Made in China 2025 strategy announced China’s intention to dominate all emerging technology, the other leading economies needed a response and the Biden administration led the way (building, to be fair, on steps taken earlier by the Trump administration).

Then on the heels of these setbacks for Beijing, the United States and the Philippines announced that new agreements had been made to expand U.S. military access to facilities in the Philippines on the southern flank of Taiwan under the bilateral Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). This agreement demonstrated that Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. has none of his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-Americanism nor any residual distrust of the United States over his own father’s ouster in the 1980s.

Beijing howled that Washington was using Asian nations against China but Xi Jinping should blame himself. China’s economic embargoes on the Philippines, Australia, Korea and others coupled with increasing military pressure and even violent attacks on India led to a convergence of concern about China’s hegemonic ambitions. Beijing hoped its intimidation tactics would slow regional alignment with the United States —and in weaker states of Southeast Asia they have — but the more influential states are choosing to integrate more with the United States and reduce their dependence on China.

But one good month does not make for a complete or even successful strategy. Korea’s Indo-Pacific strategy still needs to be implemented on the ground and Seoul will be expected to cooperate with the U.S.-Japan-Netherlands agreement on semiconductors at some point. Meanwhile, the technology agreement with India needs more than just aspirational words. And the biggest shortcoming for Biden’s strategy to date — the lack of an ambitious trade agenda — needs tending as well. For now, however, Biden has probably had his best month on Asia yet.

Copyright © 코리아중앙데일리. 무단전재 및 재배포 금지.

- Twitch to be switched off in Korea for VOD from Feb. 7

- Korean celebrities donate to help victims of earthquake in Turkey, Syria

- Korean interior minister impeached in historic vote

- Singer, actor Lee Seung-gi to marry actor Lee Da-in on April 7

- Room cafes blamed for corrupting teen morals in Korea

- BTS leaves Grammys empty-handed third year in a row

- North Korea holds military parade to celebrate Korean People's Army

- Korean rescue workers arrive in Turkey after earthquake

- Myung Ho of boy band 8TURN denies bullying allegations

- Girl group Twice's first subunit, MiSaMo, to debut in Japan in July