[Column] Fukushima disaster through eyes of subcontractor workers

이 글자크기로 변경됩니다.

(예시) 가장 빠른 뉴스가 있고 다양한 정보, 쌍방향 소통이 숨쉬는 다음뉴스를 만나보세요. 다음뉴스는 국내외 주요이슈와 실시간 속보, 문화생활 및 다양한 분야의 뉴스를 입체적으로 전달하고 있습니다.

In 2013, Minoru Ikeda reached the mandatory retirement age as a postal worker. The next year, he moved to Fukushima, where he worked for more than a year at a third-tier subcontractor for Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). The company assigned him to clean up pollution at Fukushima Daiichi and the surrounding areas.

Ikeda’s 43 years in mail delivery hadn’t prepared him at all for what he would find at Fukushima. When he left Fukushima, he was no longer the person he’d been a year before. Afterward, he wrote a book about his experiences called “Diary of Work for a Fukushima Subcontractor” and became an activist opposing nuclear power.

When he set out for Fukushima, he’d been motivated partly with the hope of helping Japan recover from the accident at Fukushima and partly with the hope of making some money. In Fukushima, his hopes came true – but only in part.

Ikeda did do work that was needed to make Fukushima inhabitable again. And the subcontractor did pay his wages each month, calculated on an hourly basis. But his worksite was governed not by science but by rule of thumb, and the pay owed to the subcontractor workers risking radiation exposure was siphoned off by invisible hands at multiple stages.

The training that Ikeda and his coworkers received before being put to work was over in a matter of hours. But even if they’d been trained more thoroughly, what was actually needed on the job was something entirely different.

They couldn’t completely remove the radiation, which was invisible. Nor could they remove the forests and fields and the nuclear reactors themselves. The goal of the cleanup seemed to be only clearing away what was within reach and moving it out of sight.

Furthermore, all they could do was stack up the scattered objects into huge piles, since — rather like spent nuclear fuel — no further disposal was possible.

TEPCO staff were hardly ever seen on the worksite. But the “invisible men” were not the TEPCO staff but the subcontractor workers themselves.

“From the perspective of the workers on the ground, TEPCO employees were like Taoist immortals hovering above the clouds,” Ikeda said. Indeed, the TEPCO staff paid little attention to either the situation on the ground or the workers themselves. These “invisible men” were at risk of injury, or even death, on the job.

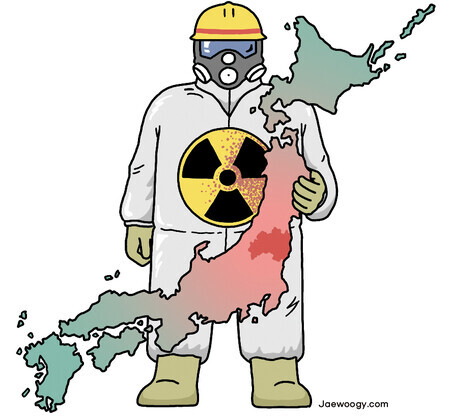

Ikeda described the workers in their white protective gear as “termites fighting against a giant” and rhetorically asked, “exactly how many millions of workers would be needed over the next 50 years?”

Without the workers at subcontractors, a nuclear plant can’t be operated or even shut down. The “outsourcing of risk” is a fundamental and unchangeable constant in the nuclear power industry.

The night the old subcontractor worker returned to Tokyo, he was shocked to see the garish lights of the city, which had once been illuminated by electricity flowing from Fukushima. Nuclear power even makes possible the outsourcing of space.

To ensure the same thing doesn’t happen to the city lights of Seoul, we need to take seriously the tragedy of Fukushima, which happened ten years ago.

By Ahn Young-choon, editorial writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Copyright © 한겨레. All rights reserved. 무단 전재, 재배포 및 크롤링 금지.

- 정세균 “변창흠 사장때 11건 투기…어떤 조치할지 심사숙고”

- 일산·분당 신도시에만 구속 131명…공직자 땅투기 32년사

- SK바이오사이언스 상장 뒤 주가 어떨까

- 김재원 “윤석열 말고 대안 있나? 악마라도 손잡아야”

- “일 못하고 도덕성 별로”…시장·구청장 만족도 24%, 의원 13%

- 엔씨소프트, ‘대졸 초임제’ 없애고 ‘시작 연봉제’ 도입

- 원희룡, 민심 뒤집고 ‘제2공항 강행’ 후폭풍…사퇴론 분출

- 구미서 숨진 3살, 외할머니가 친모였다…구속영장 신청

- 이재명 “민주당 갈등 부추기는 지상최대 이간작전 시작됐다”

- ‘진드기 목걸이’ 논란…우리 강아지 목숨 지킬 방법은?